The Gutenberg Connection

The new novel is shaping up real nice, thanks for asking. It is going to be much in the same vein as the first one, only bigger in scope and breadth. In particular, there will be a chronological component (read: history) that spans multiple centuries.

The new novel is shaping up real nice, thanks for asking. It is going to be much in the same vein as the first one, only bigger in scope and breadth. In particular, there will be a chronological component (read: history) that spans multiple centuries.

I am not going to give away the plot, but maybe I should share some of the research I did (some of it already surfaced while I was writing about the Meta Romuli). This time around, I’ll report back on the amusing time line of Gutenberg’s famous invention, movable type.

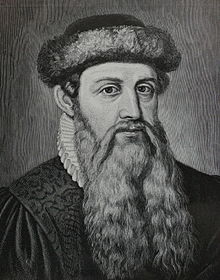

Johannes Gutenberg was a rich family’s offspring in Western Germany. His parents belonged to one of the powerful and aristocratic families of Eltville am Rhein, near Mainz. Somehow he got involved in metal working (which seems an odd occupation for a rich kid) and managed to mismanage his skill.

You’d think there isn’t a whole lot to go wrong in metal working, but apparently he overextended himself (and a bunch of co-investors). Aachen, the imperial capital of Charlemagne, was about to display its holy relics, so Gutenberg had metal mirrors made. They were to be sold as “souvenirs” to the faithful, who believed (it’s the mid-1400s, after all) that the metal could catch the holiness of the relics. (Apparently, glass mirrors wouldn’t do. Although of course the glass just protects a thin metal surface.)

As scams go, this one never worked out. A severe flood caused the cancellation of the display, and Gutenberg sat on a whole lot of expensive relic-soaking mirrors and even more debt. This was in 1439. In a bind, he claimed he had a brand new invention that would make him a rich man and allow him to repay his debt. Which, for mysterious reasons, got him off.

Gutenberg then disappears. He is sighted in Eltville, then in Strasburg, where he has family. Then he is back to Mainz, where he opens a printing shop. Soon after, in 1452, we have the first result of his printing: a flyer advertising indulgences. Then, in 1455, something incredible: a new Bible, printed beautifully, with gorgeous illustrations. Two tones, as required by a Bible: black for the text, and red for highlights and the words of Jesus.

The Gutenberg Bible was probably the very first book printed in movable type and has become a collectors’ item of immense value. The original print run was small (by today’s standards) and there are very few left. The Wikipedia page on Gutenberg Bible mentions there are 48 still in existence, with many of them only partial.

Until Gutenberg changed everything, books were being either copied by hand or printed from woodcuts. Copying by hand was interminably slow and expensive, since it required someone literate to spend an inordinate amount of time tracing lines on paper (something we are slowly forgetting, apparently). The wood cut method consisted in doing the same thing on a sheet of wood, and then taking the wood cut page and pressing it onto some kind of paper.

Gutenberg’s revolution conceptually consisted in taking the wood cut and cutting it. Imagine slicing each line of a printed page out of its surroundings. The cutting each line along the dividing line between letters. You end up with lots of equal height, small “boxes,” where each box for the same letter is virtually identical. If you now place the boxes back in order into the lines you cut out, like a little puzzle, you get movable type.

There were two big advantages in this approach: first, if you made a mistake in the old manner, you had to throw away the whole wood cut. Worse than that, once you printed a whole book, you had to decide what to do with the wood cute: keep them (and getting into a problem with the storage), or throw them away (and have to start from scratch when you need a new edition).

Of course, using the little boxes made things easier: if you made a mistake, you simply removed the offending box and replaced it with the correct one. The imprint on the page would be wrong, but paper is relatively cheap. Also, you didn’t have to worry about storage: you only needed the little boxes for the letters, and only as many of them as you needed to fit on a page. All the books in the world would be easily printed on a general matrix and a complete set of letters!

Gutenberg added to this with his particular skill: instead of using a wood matrix and wood letters, he transferred the whole process to metal. In particular, he came up with the idea of using a single cast of a letter to stamp onto a metal sheet, which would then be used as the actual letter box. The advantage of the single cast: all letters of the same type would look the same on paper. While it’s not immediately obvious that this is an improvement worth mentioning, imagine what life would look like if every single letter on a page looked different – if every “e” looked slightly different from every other “e.”

That Gutenberg would choose to typeset the Bible was a strange choice. First of all, the Bible is a relatively huge book. Printing any Bible is going to be time-consuming and require lot of capital investment and time. Here, of course, the investment is in the materials required, and the time to typeset.

Second, the Bible is the worst possible showcase of the new technology. As mentioned, the problem that movable type solved was, what to do with the woodcuts after the print run. Well, the question arose only if you didn’t know how well the book would do: for books (or prints of any kind) that were single run (like the indulgences), you didn’t need to store the matrix; for books that would do well (like a Bible) you would keep the wood cuts.

Gutenberg and his Bible suffered from the problem of cost overrun. The man managed to amass such huge debt that he lost his print shop, which went to his former partner in lieu of repayment. Gutenberg even had to leave Mainz for his native Eltville (not much of a trip, really). He helped others set up shop and fell out of favor with the powerful Archbishop of Mainz.

Later in life, people realized (not sure how) how much he contributed to printing and he was recognized. He received a title (Hofmann, which is German for courtier) and a stipend that allowed him to live out his last days in peace. He is another one of those chaps who apparently never got married (a broken marriage proposal is recorded, no marriage).

The Gutenberg Bible is mentioned starting in 1455, which is about when it must have been printed. It was an enormous success, selling out almost immediately. It was fantastically expensive, and yet gone in no time. Ironically, movable type made a second print run impossible: the effort in making a repeat possible would be almost the same as in the first place, since there were no plates stored to replicate the effort.

Movable type then spread like a crazy wildfire. In the first five years since 1455, only Gutenberg knew the tricks of the trade, and printing in movable type was done only in his home towns of Mainz, Eltville, and Strasbourg. But in the next decade, movable type spread to Paris, Cologne, Bamberg, Nurenberg, Augsburg, Basel, Venice, Bologna, Rome, and Naples. From there on, it exploded everywhere.

Frankly, I find this explosion a little suspicious. Technology innovation didn’t really travel that fast back in the day, and setting up a printing shop required capital, another commodity that doesn’t travel well (from investor to investment, that is). That movable type would reach Naples within ten years is strange: it would have required someone with the skills (and there were just a handful of people) to set up shop in town. Why would a German travel this far South?

Of course, the novel has a fancy explanation that makes sense in its context. But if you are wondering what’s so special about the towns listed above: they were giant universities. Those have always had an increased need to publish one-off documents: the doctoral theses and tractates.